The surface area of an event horizon is an extremely important quantity when calculating a black hole’s entropy.Īnd well, that brings us nicely to what this article’s intended to achieve.

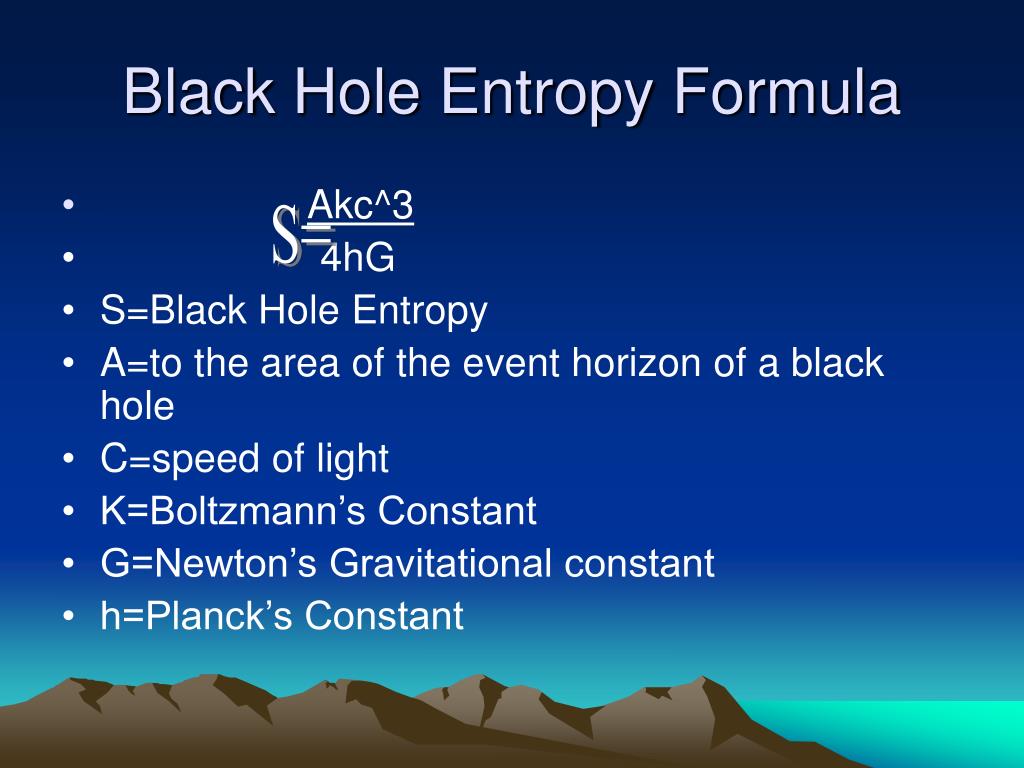

I mean, sure it’s nice to know and makes the math incredibly convenient, but the thing I really wanted to bring to your attention is that we can calculate its surface area. The fact that the black hole event horizon is a sphere isn’t too important anymore. We now refer to the entropy of a black hole as the “Bekenstein-Hawking entropy.” But he ended up actually proving Bekenstein right black holes do have entropy and temperature, and they even give off radiation. After all, if black holes have entropy then they should also have a temperature, and objects with nonzero temperatures give off blackbody radiation, but we all know that black holes are, you know, black. This annoyed Hawking, who set out to prove Bekenstein wrong. He suggested that the area of a black hole’s event horizon really is its entropy, or at least proportional to it. Jacob Bekenstein, who at the time was a graduate student working under John Wheeler at Princeton, proposed to take this analogy more seriously than the original authors had in mind.

The Second Law of Thermodynamics (“Entropy never decreases in closed systems”) was analogous to Hawking’s “area theorem”: in a collection of black holes, the total area of their event horizons never decreases over time. The story goes that in the early 1970s, James Bardeen, Brandon Carter, and Stephen Hawking pointed out an analogy between the behavior of black holes and the laws of good old thermodynamics. Albert Einstein equated the force of gravity with curves in the space-time continuum, but the curvature grows so extreme near a black hole’s center that Einstein’s equations break. These invisible spheres form when matter becomes so concentrated that everything within a certain distance gets trapped by its gravity. For decades, black holes have headlined the thought experiments that physicists seek refuge in.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)